Latest Contributions

Read More Contributions

‘Nobody gives up a job for a Sari.’ - My First Job

Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca was born and raised in a Jewish family in Mumbai. She was educated at the Queen Mary School, Mumbai, received her BA in English and French, an MA from the University of Bombay in English and American Literature, and a Master’s in Education from Oxford Brookes University, England.

She has taught English, French, and Spanish in various colleges and schools in India and overseas, in a teaching career spanning over four decades.Her first book, Family Sunday and Other Poems was published in 1989, with a second edition in 1990. She has read her poems for the All-India Radio in Mumbai, and her poem ‘Family Sunday’ was featured in an Anthology of Women’s Writing.

Her poems have also appeared in the Journal of Indian Literature, Sahitya Akademi, Harbinger Asylum, Destiny Poets, U.K, Poetry India, SETU, Café Dissensus, among others.

Kavita writes Poetry and Short Fiction. Her poem ‘How to light up a poem’ has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

She has delivered talks on Poetry and Gender Sensitization for colleges in India, and has been interviewed for a journal in Australia and IPPL, Kolkata, India.

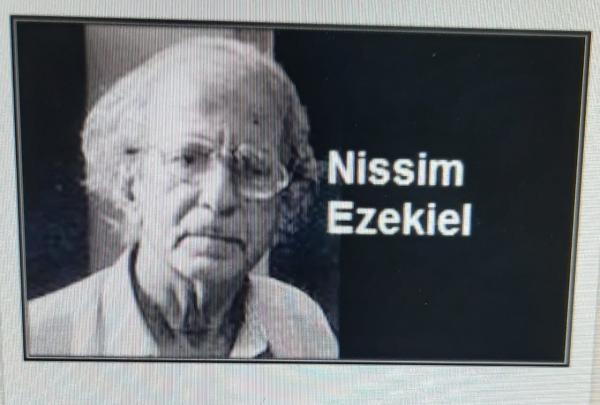

Kavita is the daughter of the late poet, Nissim Ezekiel. She manages her Poetry page at https://www.facebook.com/kemendoncapoetry/.

Affectionately dedicated to my father, the late poet, Nissim Ezekiel

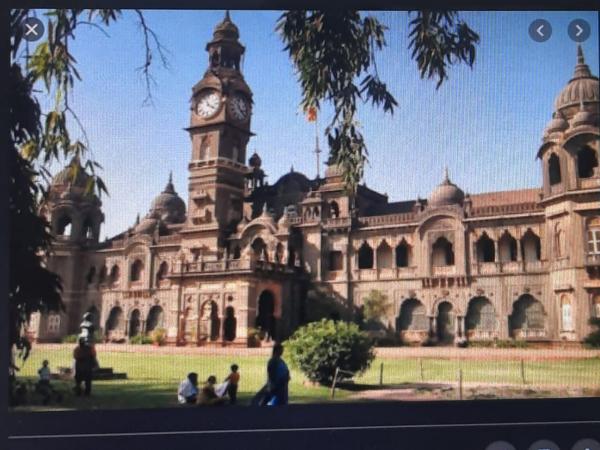

Dressing fashionably to attend St Xavier’s College in Bombay where I did my undergraduate degree was a big deal. It was a ‘hip’ place. And then there were the boys! Coming from a girls’ school, I was less excited, but more embarrassed and intimidated, very self-conscious even, all at the same time.

The one thing I struggled with apart from the presence of boys, was my extremely curly hair, aggravated by the heat and humidity of the Bombay weather. So I wore it in two braids, one I flipped to the back over my left shoulder, and the other I kept in front.

Once in a World history class, a boy placed his hand hard on the back braid, and when I leaned forward my head fell back in a kind of swinging motion. Those were the days of Flower Power and I had worn flowered hair clips at the ends of my braids, which flew to the back of the lecture hall.

Anyway, he caught my attention, and we became good friends for the rest of our college days. I had plenty of boy cousins, so that was not my first exposure to the male sex. Yet all those emotions were in so much turmoil in a sixteen year old. I fell in and out of love easily, to some professing my undying affection and they to me, which was such a thrill. Perhaps I was in love with the idea of love. We went to college so young in those days. I don’t know if I was sweet, but I was sixteen!

Next stop was the University of Bombay, where I got a little more serious about my studies, but went back as often as I could to St Xavier’s College to sing in the choir, missing some of Daddy’s lectures on American Literature, much to his chagrin. His eyes searched the room for me as he passionately explained and recited Walt Whitman to the class, but there was no sign of his daughter in the filled-to-capacity lecture hall. Those days I enjoyed singing more than Literature and I understood music better than the lofty thoughts of poets.

Upon graduating with a Master’s degree, my father and I debated the next steps of my life. He took me to a publishing house to meet a friend who was interested in hiring me. On the walk there he explained the publishing business to me and I remember breathing hard in sheer panic and confusion. The room was stacked with shelves of dusty manuscripts and I felt totally overwhelmed at the sight. The owner was a kindly woman who gave me information about the job and wanted to know when I could start. By then, I had already decided that publishing was not for me. Didn’t give myself much of a chance to learn what the publishing job would entail.

On the way out, daddy started to talk about teaching and how it was the noblest of professions. I was sold!

Actually, I had always wanted to be a teacher. I got my first lessons in teaching from my grandmother who ran a school for disadvantaged children in a slum district of Bombay.

When I was much younger, many afternoons, I would teach the leaves in the garden outside my mother’s ground floor flat and hit them with a ruler when I thought that they were not listening to me!

My grandmother explained to me that this was not the way to teach, and that love, patience and kindly explanations would help a child learn better than corporal punishment. My grandmother had been trained by Maria Montessori, but love and kindness were already in her blood. My father and mother were both teachers, my mother of the stricter variety (teaching Math, as opposed to Shakespeare, required firm handling), my father, poetic and patient.

I began to interview for teaching positions and obtained a job in the English Department in an Arts and Science College. At the end of the interview the Principal looked me up and down (I thought I might not have succeeded in getting the job), and said, ’you have the job, but you will have to wear a sari if you want to teach here.’’ I had gone to the interview dressed in bell bottoms and a kurta, a sort of longish shirt with, what I believed to be of a modest design for the interview.

I had never before worn a sari. And the job was to be an initiation into its intricacies. An aunt who lived with me gladly took me to the sari shop and we purchased three or four saris and some readymade petticoats, and blouse pieces to be tailored to my measurements.

She then proceeded to sew on the falls on the saris. Whatever would I have done without my aunt! She was the essence of kindness and understanding. She also taught me how to drape the saris with unimaginable patience.

The first days of the job in my new garb, were challenging, to say the least. Standing on a high podium, reached with the help of a wobbly step, in a sari, with 150 students in front of me, calling out the roll (attendance by number) for 20 minutes of a 45-minute English class was not what I had signed up for!

English was a second language for most of the students and there were often students waiting for me after class for more explanations of concepts they had not understood during the lecture.

I prayed the sari would hold on until I got back to the Staff room. The biggest highlight of my two years there were the teaching staff. They were such genial personalities, laughed a lot, and treated each other with love and respect.I was the youngest member of a fourteen-member English department, with a wonderful Head of Department who took me under her wing imparting lessons in life and in teaching. If I wore a green sari, one professor would greet me with a ‘How green is my Valley!’ There was a famous Marathi poet on the faculty, and she used to quote lines from her poetry that matched the mood my sari created for her. What a treat!

Other compliments followed, but always they were humorous, kind and gracious. I began to feel a little more comfortable in my sari. Also, there were friends to help with redoing the pleats of the sari in the college washroom, which was the tiniest of places two girls could squeeze into, but it did have a standing mirror. The class started promptly at 7:15 am so the sari must be in place on time. I was teaching, what they called, ‘Morning College’.

However, there were two unnerving incidents which turned me off saris forever.

The first one occurred when I was waiting for my bus to arrive in my freshly-washed and ironed white sari. It was a double-decker bus and a man sitting on the top deck suddenly spat out the blood red betel juice of paan he had been chewing. I watched him in horror but was helpless to stop the stream of spittle.I looked down at my sari at the rapidly running red betel juice as it blotched the right side of my sari with a large blood-red stain.

Luckily I had a late lecture that day, and could run back home to change into a different sari that was hanging in the cupboard.

I got to work and narrated the unhappy incident to my fellow colleagues who replied that spitting was common in our country! They said I shouldn’t be surprised if it happened again.

The stain on the sari never went away and, sadly, the sari had to be discarded. Subsequently, I always first looked up when the double-decker bus arrived to see if there was a paan-chewing man who would shower me with the juice of his paan. I was haunted by the experience.

In fact, I was quite traumatized.

The second incident occurred when I was in the bus on my way to take a seat. The bus was very crowded with construction workers and somebody stepped on my pleats.All of them came cascading down onto the floor of the bus. Much embarrassed, I quickly gathered the falling material and tried to tuck as many pleats back into my petticoat as I could, looking around to see if anyone had noticed.

When I got off the bus I ran to the college washroom and proceeded to re-do the sari. I was in tears, of course. It was so hot, the saree clung to my skin which made it even harder to drape. I hoped that neither any of the staff or students would see my flushed cheeks and ask if anything was wrong.

When father got home that night, I told him that I was going to give up my teaching job. He looked a little puzzled and asked me why I wanted to give up, as I had just started the job.

I narrated the two incidents to him and said that it was all because of the sari I had to wear to work. I could not do the job any longer if it meant I had to wear a sari to teach. I found it hard not to cry while narrating my challenges.

My father laughed in amusement. His delicately balanced glasses shook a little.

‘Nobody gives up a job for a sari,’ he announced.

I don’t think he understood my plight. He said he would walk me to the bus stop, as if that would help. But, that was daddy! He said, if it were necessary (his favorite phrase), he would even take the bus with me all the way to the college, but on no account was I to give up teaching. Again that was daddy for you! Imagine taking your grown up daughter to her place of work. If anyone saw him (he was easily recognizable), what would they think of me?

So, I bought a large safety pin and pinned all the pleats together before tucking them into my petticoat and I also pinned the pallu of my sari to my blouse to prevent it falling off my shoulder.I taught in that college for two years, and always wore a sari to work, pins and all!

My next two jobs also required me to wear a sari and I continued to struggle with the six yards to be wrapped around my tiny frame.

Now, I wear a sari only on very special occasions. I prefer to wear the Salwar Kameez, which can be easily slipped on. I know that saris are graceful and beautiful but perhaps just not in my destiny!

Copyright @ Kavita 2021

Comments

Six yards of beauty and misery!

Amusing it is; at the same time brings out the anxiety of wearing a sari, if you are not used to it. Ms Kavita deserves our best wishes for enduring the agony for two years.

Interesting anecdote ! And

Interesting anecdote ! And the description takes you back right to the days of yore

A Good read.

A Good read.

Saris

Such a lovely story. The sari is not easy-wear, that's for sure - even I, as a man, knows that. BTW. Indian air hostesses have long done what you did to wear saris, starting from the 1950s.

I have read the above article

I have read the above article . overall it definitely is a novel concept ie Job vs Saree . Saree , definitely is a great attire but many women must be facing similar awkward circumstances as explained in this article . Therefore in my view something be it a saree , howsoever Indian in look , should not be thrusted as a requirement for a job.

two quotes really impressed me in this article :-

I was in love with the idea of love -

I understand music better than lofty thoughts of poet-

Add new comment