My Memories of Mussoorie

Anuradha Joshi belongs to Kumaon. A postgraduate in Psychology from Rajasthan University, she taught in various schools and colleges in Kolkata.

Currently, Anuradha lives in Mussoorie with her husband, Pawan K. Gupta.

In 1989, along with her husband she co- founded SIDH (Society for Integrated Development of the Himalayas), largely working in the villages of Tehri Garhwal, to make education more relevant to the local needs.

My tryst with Mussoorie began when I was fifteen years old.

I was sent to Mussoorie to complete my final years of schooling. I was also staying away from home with my grandparents who just let me be. That itself was liberating. I was living without the tension created by my strict authoritarian father or my over-anxious mother who had only two standard replies to all requests that were rejected: “What will people say? “or “This doesn’t happen in our house.“

I never felt so happy and free to be myself. I connected this freedom and joy to Mussoorie. And so, Mussoorie became my first love.

When I was staying with my grandparents, I would often wander outside the house and look with awe at the tall deodars. One day, I wandered a little further, my foot slipped and I found myself rolling down. I was wondering whether I would continue rolling down to the stream at the bottom of the hill, when I found the rolling had stopped and I was in a beautiful meadow, all by myself with two tall deodars for company.

I was completely besotted by the sheer beauty and the wonder of the whole experience. That is how I literally fell head over heels in love with Mussoorie! The meadow, the mountains, the mist, the deodars, the fresh air, the silence, the space, just about everything was a visual delight. After that I often returned to this sacred space. I would sit and write in my diary to myself. Some of them were poems about the wonder of life. This experience of wonder and beauty now had a name - Mussoorie. This was home. I knew I would always return to this place.

And I did.

So here are the stories I have been entertaining my friends and family with for a long time — about Mussoorie, my great love — and about the people I knew during my early days here. I certainly intend to enjoy myself in the process in relating these stories.

- Bappi, my great grandfather, Shri Ramdutt Joshi (1872–1962)

- Netramani, caretaker of Bappi's house in Mussoorie

- Babban, my maternal grandfather, Shri Kanti Ballabh Pant (1900–1983)

- Chachi, my maternal grandmother, Smt. Ganga Devi (1910–1990)

- Babban's life as a public figure in Kumaon

- Babban and Chachi, my maternal grandparents, as homemakers

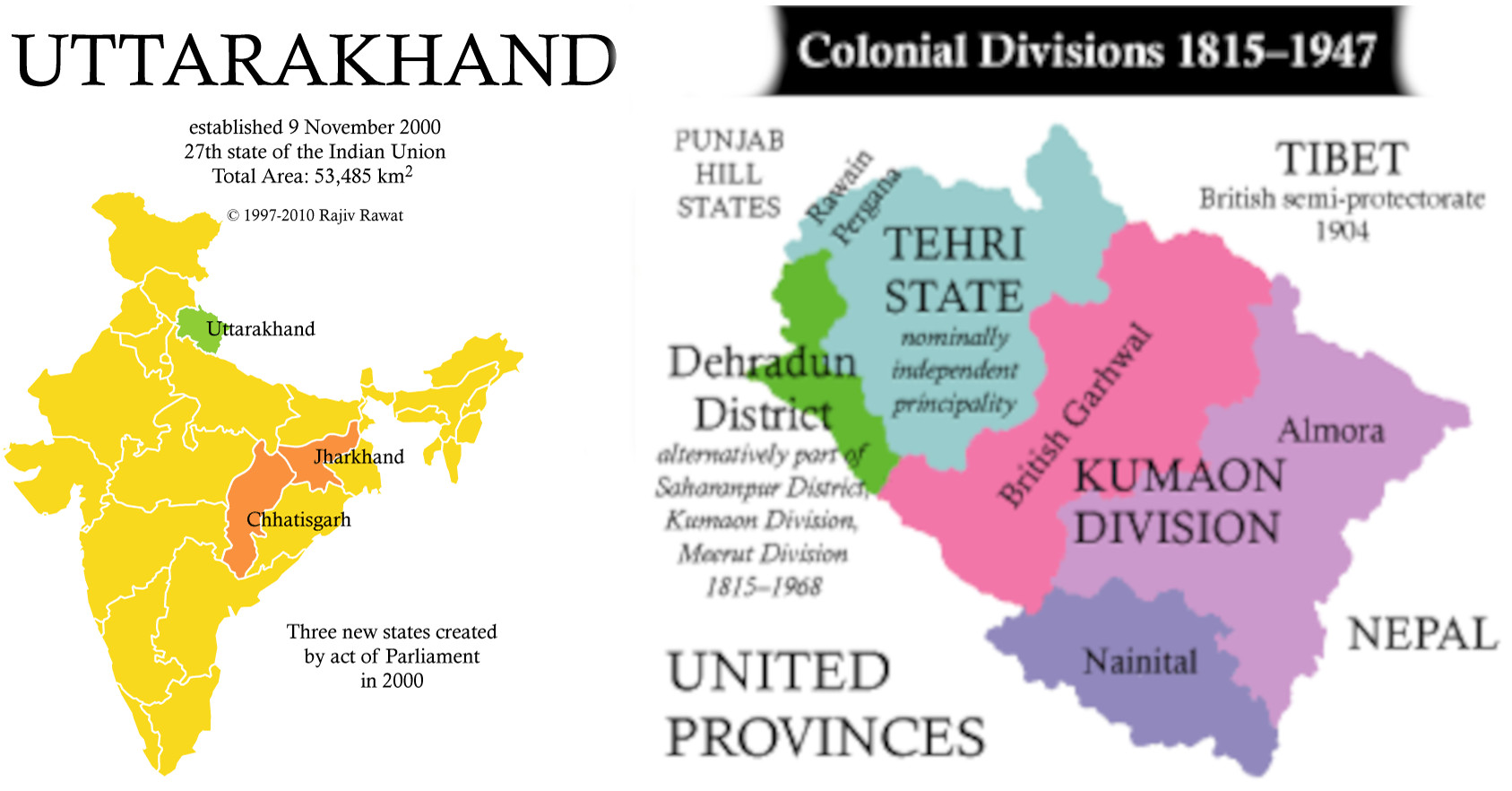

The main geographical divisions of Uttarakhand before formal statehood: Tehri, Garhwal and Kumaon. (Map 1815–1947)

Bappi

I remember coming to Mussoorie every summer as a small child. My great grandfather, Shri Ramdutt Joshi (1872–1962), was called Bappi by everyone – his family, children, grandchildren and even by neighbours. He was a very picturesque character. Small built, very active and alert, he always wore a khadi topi on his head, rounded with use and framed by his silver colored hair which curled around the edges of his topi giving him quite a theatrical look. Despite his age, (I am assuming he must have been above eighty at that time) he was undoubtedly the master of the house.

Every morning, with his hands at the back, he would walk confidently around the large house, looking into every room – including the kitchen – his sharp eyes noticing everyone and everything.

His wife had died several years ago. None of my grandaunts spoke of her much, even in passing. Bappi was both the master and the housewife and felt responsible for the general running of the house, which could easily have 30-35 people of his extended family staying there, at any given point of time. Apart from the visitors during the two summer months, many of my younger uncles and cousins also stayed there all through the year, till they passed out of school.

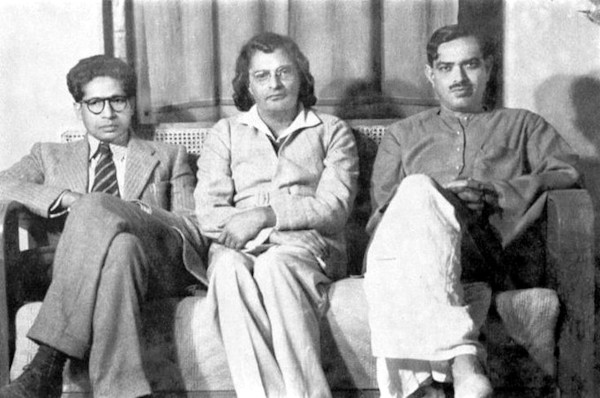

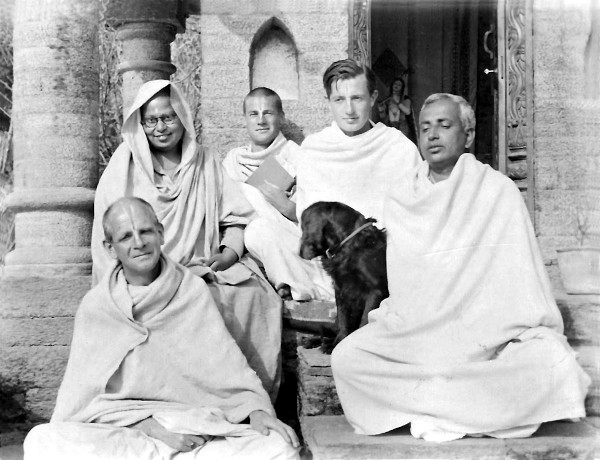

Anuradha Joshi as a young girl at Bappi's house, Fern Lodge in Barlowganj, Mussoorie, surrounded by her uncles. On the extreme right is her grandfather, Babban.

He never raised his voice while talking, and always spoke clearly and slowly, in a courteous manner, with even those who helped in the kitchen or cleaning the house. Once I overheard his comment when he went into the kitchen. He probably wanted to draw the attention of the cook’s helper, to the fact that he was not cleaning the rice and grains properly. So very slowly and softly he said “Bula (young boy), I think you like the taste of small stones and ‘matti’ in your food. We don’t. So please remove all the stones and matti when you are cleaning and washing the food grains, before it is cooked. When you eat, you can sprinkle some stones on your thali.”

I was quite amused at the way he reprimanded Bula, the young helper, who in turn hid a smile and was also taken aback. This is how he would speak to all of us. Whatever he had to say was communicated very simply and clearly. I realised that it’s true when people say that anger doesn’t resolve problems. We get angry and raise our voice only when we are unable to communicate to others. Probably, our frustration turns to anger and makes matters worse.

During those days privacy was not a priority or a necessity as it is today. In the hills the houses were large, with many rooms leading one into another, with no attached toilets but with a set of bathrooms and toilets at one end of the house. Most of the family members happily shared whatever place or bed they were able to get.

All the children would really enjoy this game, especially when we had an overflow of visitors. Extra mattresses would be laid out on the floor of the large living room and it was fun because sure enough someone would begin a ghost story and we would be both fascinated and fearful in turns. During every long pause in the narration, we would hug one another when scared or prompt the storyteller with an impatient, “And then? And then what happened?”

After Bappi finished his round of the whole house in the morning, he would go and sit in the large living room and ask for some family member or the other and speak to them one by one in private. During summer we were three to four generations staying together in the house; the senior group: of Bappi’s daughters (my grandmother and her sisters), the middle group: of my mother and her sisters and cousins, the youth group: of unmarried uncles and aunts and the junior most group comprising of all of us: the children.

The kitchen at Bappi's house, Fern Lodge. Seated are Bappi's daughters (from L to R): Lakshmi Devi, Devaki Devi and Ganga Devi.

The family sunning themselves in the garden at Fern Lodge.

The children in the garden at Fern Lodge.

Our group was always curious about who was summoned by Bappi and we had a lot of speculation among us about why they were called; and sometimes the youngest among the children, was also encouraged to eavesdrop into the conversation.

I remember a very amusing incident we overheard about Beena Didi. She was much older than all of us. She had just got her college result and had done well. Her father had sent her a money order of Rs 50/- which was a princely amount for that time. My younger uncles and aunts insisted she take them to the Mall road for coffee to celebrate the good news. She herself may have felt a little unhappy about parting with her gift money. But she complied under a lot of pressure. A dozen of the older cousins went happily on this excursion.

Bappi heard about this jaunt. The next morning Beena Didi was called into the living room by him and was told : that she should not have wasted all her money on something like coffee. Beena Didi was probably regretting having spent all her pin money by now. So when Bappi reprimanded her she just burst into tears and said she was ‘forced’ to give everyone a treat. Then all those who had gone to the Mall were called in and Bappi asked that the total amount of the money spent would be divided equally amongst the merry makers, and each one had to return the cost of his or her coffee. They did so. But the matter did not end there.

When Beena Didi got all her money back, one bright young cousin came to the conclusion that the money returned to her included the cost of her own coffee too! At this point, Beena Didi who was feeling not nice about accepting the money, burst into another round of tears and literally threw all the money collected in small coins at everyone. This was high drama. I don’t recall how Bappi resolved this exhibition of temper as tantrums rarely happened in Bappi’s presence. All I do remember is that our children’s group in particular, savoured this incident with great glee for many days, all the more because our group had missed out on the excursion to Mall road, so now thoroughly enjoyed the gossip.

This is just a small example of the dynamics that were present in our Mussoorie family get-togethers, under Bappi’s eagle eye.

Netramani

I first met Netramani in my great grandfather's large rambling house in Mussoorie when I was little more than 7 years old. During those days personal cars were few and far between; tourists usually travelled by bus to the hill stations. It was a common practice for house owners to employ a few labourers who stayed on premises, where they were provided board and lodging; in return they did odd jobs like working in the garden, carrying the monthly store of groceries and foodstuff from the market as well as carrying the luggage of guests and family members who flocked to hill stations to escape the summer heat.

Netramani lived in the room below the kitchen with two other men, but he seemed different from them. He was of stocky build and always had a thick rope tied around his waist. He had only one good eye, while the injured eye always remained half shut. But he bore this loss with so much dignity that no one, not even his young friends would ever make fun of him. For some strange reason his deadpan expression, and silent demeanor made everyone respect him far more.

Whenever Netramani was asked a question, he would open his mouth as if he was about to reply, then shut it, raise his head, shrug and say “Kya karna?”, which sounded more like one word, “Kyukkarna”, like the clucking of a hen. That was all that one could get from him in terms of a response. That was his answer to almost every question.

I used to follow him around the garden while he worked. Although he hardly spoke, I was drawn to him, by his quiet presence and a sense of security around him. I was also very curious. Finally my curiosity got the better of me and I asked him about it. Wearing his usual deadpan expression his reply was one just one short sentence; that as a little child, he stumbled into a thorny bush, while following his mother in the forest. That’s all. I had many questions but they seemed meaningless as I watched him continue weeding the flower beds.

Netramani firmly believed that he needed only Rs. 5/- a day for his needs, which he earned as a tip from a guest each time he carried their luggage to the bus stop. The opportunity to earn money came only during the 2 or 3 summer months.

Netramani had earned a lot of goodwill with everyone in the family. So whenever there was more than one trip to the bus stop, Netramani was pressed upon by many in the family to make that extra trip to earn extra money. But he was very stubborn about this. He said he did not need more than Rs 5/- a day. Nothing would make him change his mind. Many family members would ask him to save that money for winter days, when the house would be locked up and the kitchen closed. He would merely shrug and say “Kyukkarna?”

As I grew older I too was concerned about Netramani and how he would survive the winter months. The house was closed down for winter and most people who worked in the house would go to their villages as Mussoorie could get extremely cold. Netramani stayed on. When we asked him why he did not go to his village, he would again shrug and say “Kyukkarna?”

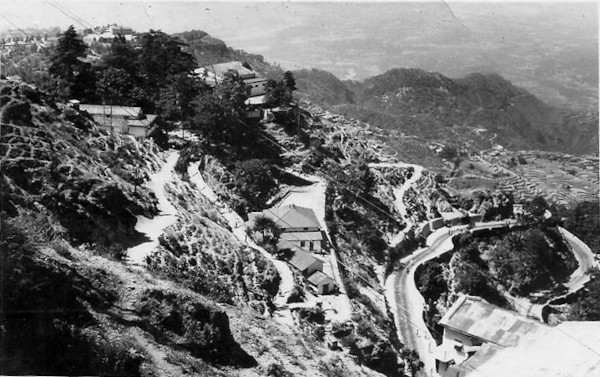

The view from Fern Lodge during winters in Mussoorie. The hill sides are covered in snow. Doon Valley and the Shivaliks are visible in the distance.

Year after year, each summer we saw him looking exactly the same. Times had changed. Roads had made it possible for motorcars to come almost to the houses. Netramani was not needed to carry the luggage of guests to the bus stop. But he continued working silently in the afternoon in the same way around the house.

Once I asked him how he survived the winters without any money or food. He said that was simple. He used to walk down every day to a dry river bed with a small tin pan and collect the smooth round stones from the river bed. He would then make a fire and boil the stones for an hour or so and then drink the water. That was enough to get him through the cold winter days. “Was that all?”, I asked him. He nodded and said “Kyukkarna?”

Babban

I cannot think of Mussoorie without my mother’s father, Shri Kanti Ballabh Pant (1900–1983), known as Babban to all. He made a huge impact upon my life. My memories of the wonderful days spent with him got transferred onto a place instead of a person and made Mussoorie the love of my life.

The innumerable poems that I wrote during my exile from Mussoorie are proof enough how passionately I longed to be there; until reaching that small hill town became my most coveted dream. Almost as if I knew that I would be begin to live that line from Babban’s poem titled Santavana: “Bas vahin tak hai pahunchna / Paar uske pyar hai” (I just have to reach till there; beyond that is love).

Sure enough, when one is obsessed with a dream it always turns into reality. So I’ m not at all surprised that even after 30 years, I wake up each morning with a feeling of deep gratitude for simply being in Mussoorie.

Babban was a man of many interests and many talents. Apart from Sanskrit, English, Hindi and the Kumaoni dialect, he knew Bengali, Urdu and also Farsee. He wrote in all these languages and Kumaoni too. He was a poet, a writer, an artist, a musician, he could play any musical instrument which he taught others too. I met many people from Almora who told me how Babban had taught them the violin, the sitar or the flute. He was the secretary of the famous Hukka club which was really the cultural hub of Almora.

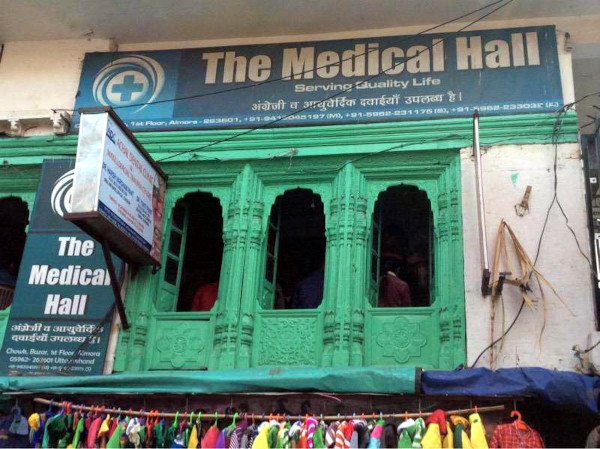

There are two parts to this story about Babban, each based on very different perspectives. Babban, as seen through my mothers’ eyes, was the young father, the breadwinner and a very charismatic figure. This is the time when he was in Almora, and an extremely outgoing person, with friends from different walks of life. He looked after the pharmacy called “Medical Hall“ in the main market in Almora, which turned into a venue for many of his friends with serious literary and spiritual pursuits to come together, in the late evening. He was centre stage here and contributed to the rich cultural diversity of Almora.

Medical Hall, a pharmacy run by the family, in Chowk Bazaar, Almora.

A view of the first floor of Medical Hall, a pharmacy run by the family, in Chowk Bazaar, Almora.

I never knew this Babban at all.

My memories of Babban are of the quintessential homemaker, and restricted to the time I spent in Mussoorie with Babban and my grandmother, Smt. Ganga Devi, known to all as Chachi.

I remember Babban as an elderly grandfather, a very private person, a Sanskrit scholar, a poet and a musician, full of humour – the kind of humour which, on more than one occasion, he would turn on himself. He always had a very positive outlook even though he was struggling with failing eyesight, which handicapped his writing a lot. He disliked sympathy; his favourite line was “Andhaa aadmi bhi sapne to dekh hi sakta hai” (Even a blind man can see dreams).

When I think of him I see the picture of a tall, erect, fastidious, well dressed man, full of confidence; of course he needed to walk with the help of a walking stick but nothing in his demeanor betrayed the fact that he could not see properly. He was also a man totally focused on his home and family.

Chachi, his wife, his constant companion, took care of him with her quiet support. He could not function without her.

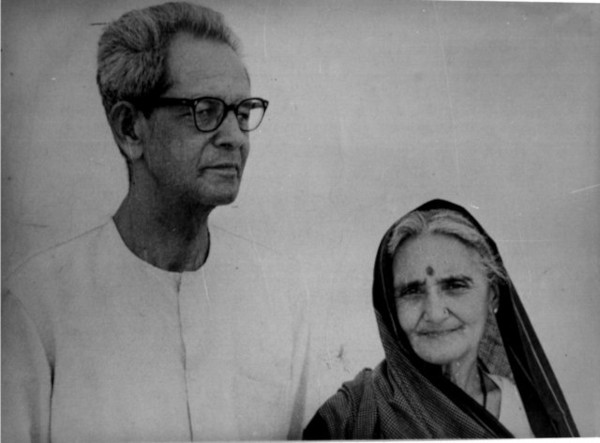

Anuradha Joshi's maternal grand parents: Shri Kanti Ballabh Pant ("Babban") and Smt. Ganga Devi ("Chachiji").

Chachi

Chachi, my maternal grandmother, Smt. Ganga Devi (1910–1990), was possibly the strongest and most practical person in the family: quiet, active, and happiest when she had something to do with her hands.

Babban and Chachi were completely opposite in nature. Babban was creative, multi-talented, a perfectionist, over sensitive, had many interests, and loved to think, analyse and speculate. Whether it was a word, a person or an event he would deconstruct it till it was threadbare. He loved to talk and spoke well. Yet despite his spiritual leanings and philosophical outlook he was constantly fearful and anxious about the well being of his family.

Chachi on the other hand, was stoical, pragmatic and fearless. A woman of few words she enjoyed working in the kitchen, cooking and even cleaning. She was very unhappy with the work done by the help at home, who washed clothes or cleaned the utensils. She would go on a round after lunch and check all the clothes and if dirty would scrub them clean all over again.

She loved sports and games of any kind. She rarely got the time to indulge in these activities, but whenever she got a chance to play she never let go of the opportunity.

Usually after lunch, after all her work was done, instead of resting, she would join her grandchildren in whatever game they were playing; it could be carrom, cards, and board games like ludo, snakes and ladders and monopoly – she was good at all these indoor games. But what she loved most were the outdoor sports, like cricket, badminton, table tennis, and other ball games. Everyone wanted Chachi as their partner.

She loved adventure too, and going to see the circus and magic shows. Whenever we went to see the circus or magic shows, it was only Chachi who would happily accompany the children and thoroughly enjoy herself.

Babban: the public figure

My mother, Prema

Anuradha Joshi's mother, Prema.

My mother, Prema Pant, was Babban's eldest daughter. She grew up in Almora. After schooling, she did her graduation from Bareilly.

She married Raghunandan Joshi who was a member of an organised civil service with the central government.

She moved around with her husband to several cities in India and abroad as per his postings. She has been a house wife all along.

She has published three books for children. One, a book about local food called "Kumaoni Bhojan". The second, a book on Kumaoni folklore. The third one was on the different rituals and festivals of the hills called “Hamare Teej Tyohaar."

After the death of her husband, she lives in Lucknow.

Gandhi and Tagore at Almora

I will begin with my mothers’ narrative about her family home in Almora. Much of what I’m writing is what my mother remembered and told me. It is fascinating in its own way because it is also a record of dignitaries like Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) and Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), who visited Almora during those days.

When Gandhiji came to Almora in June 1929, Babban was asked to read the welcome address in a public meeting. Naturally this must have been a very memorable event that stayed with everyone in Almora.

The ashram at Kausani where Mahatma Gandhi stayed for 2 weeks in 1929. Gandhiji wrote his treatise on detachment (anasakti) here. The ashram was subsequently renamed Anasakti Ashram.

Babban was also a good mimic, and would reproduce extracts of Gandhiji’s speech much later, even for my benefit. I remember asking him to keep repeating it, till his audience would get a bit tired and ask him to stop!

Mahatma Gandhi at Almora where the Almora Nagar Palika presented him with a felicitation paper on June 18, 1929. Photo courtesy Rajiv Lochan Shah.

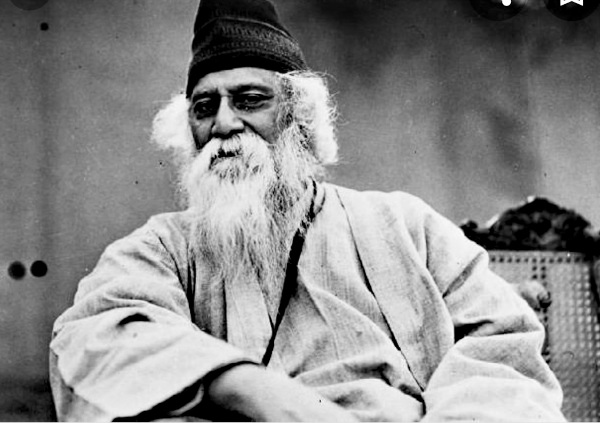

It seems that elaborate preparations were made when Rabindranath Tagore visited Almora in May 1937.

Several rehearsals took place of the cultural event that was to be held in his honour. Babban was to give the welcome address. He wrote a beautiful poem in Bengali in honour of the great poet:

Kobita nolini shekhane jabe

Jekhane kobi Robi

Pushp jogote harsh holo

Nolini peye chobi

He composed the music for it and my mother and aunt rehearsed this song to sing before the poet.

However, Sumitranandan Pant did not like this idea. He was a well-known Hindi poet and Babban’s school friend. They had studied together and shared similar sensibilities.

Pantji argued that however good Babban’s Bengali may have been, singing a Bengali song before Tagore, the world-renowned poet, was just not done. So the original plan was vetoed at the last minute.

Instead, my mother and my aunt sang a traditional bhajan in Raga Piloo. ”Sumiran kar le, mere mana”. My mother remembers garlanding Tagore who blessed her by placing his hand on her head and cheek. She said his hands were very soft. It was a memorable day for her.

Rabindranath Tagore

Tagore Bhavan in Almora's cantonment area, where Rabindranath Tagore stayed in the summer of 1937 and composed several poems that were later included in the anthologies titled Senjuti (1938), Akash Pradip (1939) and Nabajatak (1940).

Sumitranandan Pant at Kausani

Sumitranandan Pant (1900–1977) was a well-known Hindi poet who was born in Kausani. He and Babban were old school friends.

The stone cottage in Kausani where Sumitranandan Pant was born, a government museum today.

They would design their clothes together – especially their coats – in ways that was very different from the current fashion. Pantji would often share his recent writings with Babban.

On his birthday, Babban wrote a poem dedicated to him titled “Tum bhi kya gaa sakti ho sakhi?“ This was a special poem, containing all the titles of Sumitranandan Pantji’s various publications till then, like Pallav (1926), Gunjan, Beena, Jyotsna. An example of the poem:

Pallav se hote lav

Gunjan hota jeevan geet

hriday tantra hi Beena hoti

Jyotsna pati fenojjval meet

Virah to main gaa hi leti

Shvason ke taaron ko kheench

In Almora, Babban took care of a pharmacy called Medical Hall, a family concern, which in the evening would turn into a literary or cultural hub, filled with like-minded friends.

Sumitranandan Pant would often be found sitting there, wearing a crochet cap, usually made by one my aunts. My mother and her siblings often sat in “Medical Hall“ and Pantji would help them with their Hindi homework!

Sometime later when Pantji was staying temporarily in Kausani in a small cottage he invited Babban to come there. They worked together on a literary magazine called Rupaabh, whose first monthly edition came out in July 1938.

Later, they stayed in touch, writing to each other, only in postcards. When Pantji shifted to Allahabad in 1944, he was keen that Babban come there too, as he felt it was a good place for poets and creative people. But by then Babban was facing a lot of personal constraints and family responsibilities, so he declined this offer.

Sumitranandan Pant (centre) with other well-known Hindi poets in Allahabad. On the left is Harivanshrai Bachchan and on the right, Ramdhari Singh Dinkar.

Babban and Pantji always kept in touch, writing to each other on postcards. I remember posting Babban’s letter of congratulations to Pantji when he received the Gyaanpeeth award in 1968. Babban promptly got a reply – again a postcard.

Earl and Achsah Brewster at Simtola

Another friend of Babban’s was Earl Henry Brewster (1878–1957), an American artist who lived in Simtola with his wife, Achsah Barlow Brewster (1879–1945).

The Brewsters shifted to Simtola in 1935 and lived in a house on a pine-covered ridge located on the way to Kasar Devi temple.

Babban would often go to their house and take my mother and her sister along. When my mother met the elderly couple, she noticed that the Brewsters had spread thick woollen blankets called thulma (made of sheep wool), on the floor and were also wearing clothes made from these thick blankets. Brewster wore a pair of trousers and a coat and his wife wore a long gown – both made out of thulma.

American artist Earl Brewster meeting visitors at his house in Simtola.

My mother also recalls seeing a huge, black stone statue of Buddha, sitting in the pose of meditation, placed in the inner room of their house. There would always be a big bowl made of ‘kansa’ with fresh roses, in front of this statue as an offering. Next to it was a traditional brass box, made of jali work, (the kind that was commonly used to carry tiny replicas of gods and goddesses when families traveled from Almora). His wife would fill this little box with peanuts and serve it to guests. My mother and her sister enjoyed these peanuts a number of times.

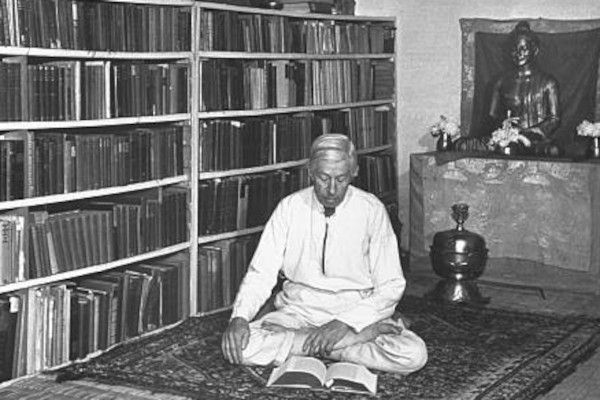

Earl Brewster seated on the floor in front of a statue of Buddha at his house in Simtola.

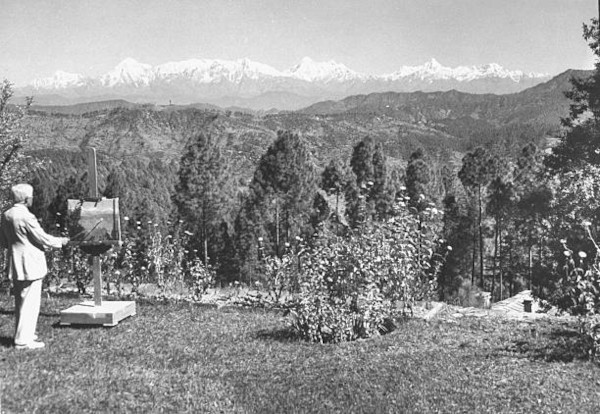

There was a fantastic view of the Himalaya from their house, which was the subject of most of his paintings. Naturally, many of these paintings were stacked along the wall of his cottage. He loved to give his paintings to friends, if they liked them. Babban liked the paintings but did not take any of them. One can see many of Brewsters’ paintings proudly displayed in many homes in Almora, even today.

Earl Brewster painting in the garden of his house in Simtola from where he had a clear view of Nanda Devi, the highest peak in Uttarakhand.

An oil painting by Earl Brewster titled Trishul and Nanda Devi Before Sunrise with Autumn Cherry Blossoms.

Uday Shankar’s Centre at Almora

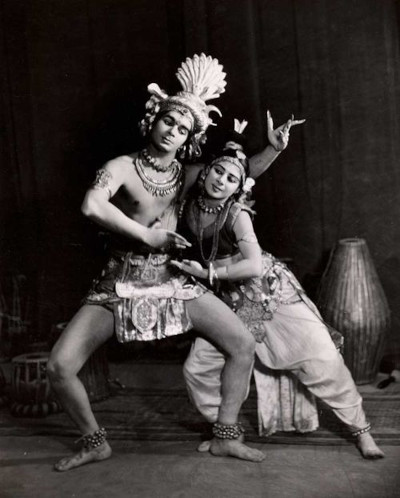

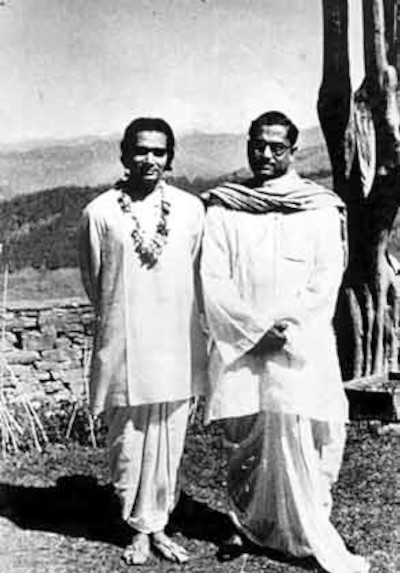

Uday Shankar (1900–1977) was a dancer who had performed in Europe and America with his own dance troupe, 'Uday Shankar and his Hindu Ballet', during the 1930s. Rabindranath Tagore persuaded him to set up a performing arts school in India.

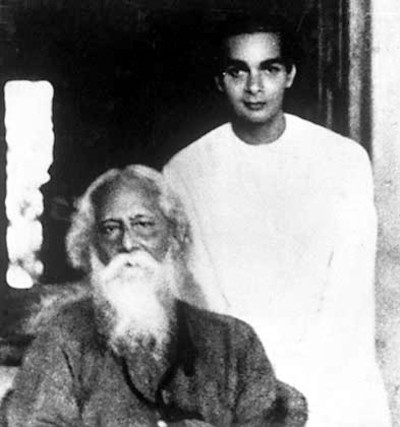

Rabindranath Tagore with Uday Shankar. This photo was taken in Calcutta shortly before Tagore's death in 1941.

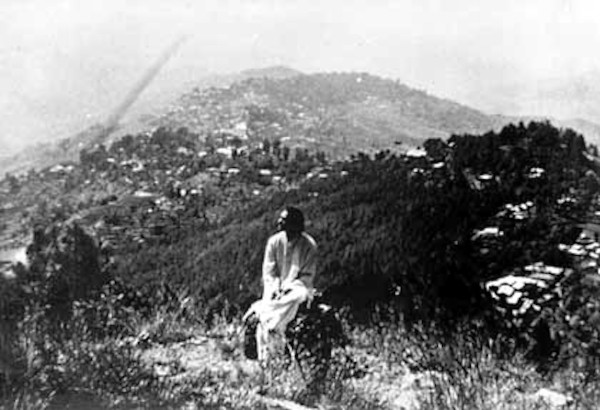

Uday Shankar on a 1938 visit to Almora to select a site for his culture centre. He finally chose an abandoned, eight-acre tea estate with heavenly views of the snow-crested peaks around Nanda Devi.

Uday Shankar had a charismatic personality. His eyes were magnetic. People were drawn to him. There was something divine, almost god-like about his face. Whenever he would walk in the streets of Almora Bazaar, wearing a dhoti kurta, people would throng just to get a glimpse of him exactly as crowds of people come to see a film star or a cricketer today.

When Uday Shankar came to Kumaon and set up his cultural centre, Babban was a frequent visitor and would always take his children along. My mother remembers how excited they would be to attend the functions at the Centre, and how important they felt to sit “right in the front row”.

The main studio at Simtola, 3 km from Almora town, of the Uday Shankar India Culture Centre.

An outdoor workshop at the Uday Shankar India Culture Centre, Almora.

Indoor stage rehearsals at the Uday Shankar India Culture Centre, Almora.

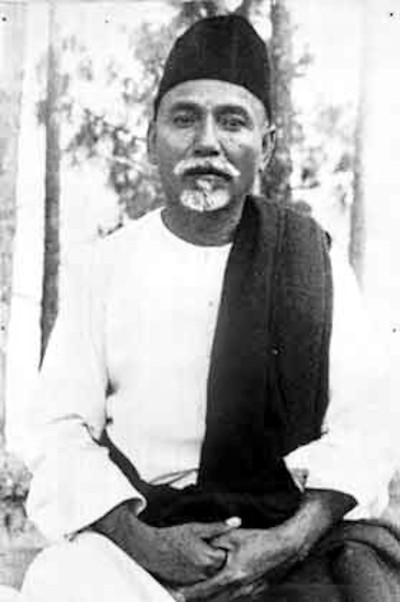

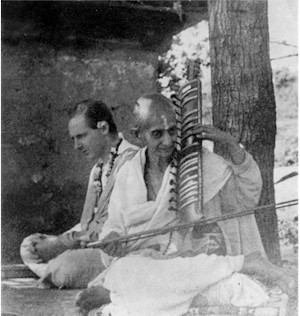

Ustad Allauddin Khan (1862–1972), a sarod player and multi-instrumentalist, served as a teacher of Indian classical music at the Uday Shankar India Culture Centre, Almora.

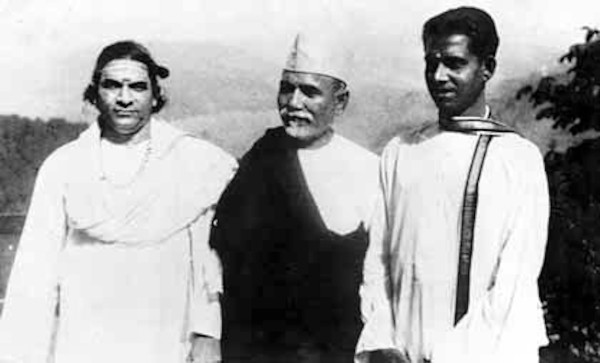

Ustad Allauddin Khan (centre) flanked by dance teachers at the culture centre: Guru Sankaran Namboodri (Kathakali) on the left and Guru Kandappa Pillai (Bharatanatyam) on the right.

Guru Maisnam Amubi Singh taught Manipuri dance at the culture centre.

Babban knew all the performers and so the children too, met people like Zohra, Simkie, Uzra, Laxmi Sastri, Ravi Shankar, Alauddin Khan Saheb, Kichlu brothers, Guru Dutt, Vishnu Dass Shirali (who played the jal tarang) and V. G. Jog (who played the violin and received substantial training from Ustad Alauddin Khan). As Babban was fluent in Bengali, he helped many of these artistes to do their shopping when they went to the local market.

Uday Shankar brought his dance troupe to Almora to serve as teachers at the culture centre, seen here just before their departure for New York in 1937.

In the forefront, at the bottom of the stairs are sisters Zohra and Uzra. Standing between them is French dancer, Simkie (real name Simone Barbier). Directly behind Simkie stands Vishnu Dass Shirali who played the tabla taranga and mridanga. To his left and partially hidden is Uday Shankar's cousin, Kanak-Lata, a dancer. To his right is Uday Shankar.

Towards the back are Uday's brothers, Debendra, Rajendra and Robindra; and sarod player, Timir Baran Bhattacharya.

The culture centre opened in March 1940 with 10 students, seen here with the full staff. The number of students eventually ramped up to 60.

My mother vividly remembers the Shiv Tandav dance performance, with Uday Shankar and Simkie dressed as Shiv and Parvati. They also performed a ghasiyari dance, wearing local costumes, based on the lives of the village women near Almora. These performances were very different from what was usually seen in local theatre.

Uday Shankar with Simkie as Shiv and Parvati.

Impresario Haren Ghosh (right) who first introduced presented Uday Shankar (left) and his innovative ballets to the Indian public in 1930.

The Ramlila was performed at the Centre in chaaya nritya style - in shadow, so one only saw the outlines of dancers behind a thin transparent cloth, dancing on stage. After that a Ram Baraat was taken onto the streets. All the performers would dress up according to the characters they were playing and go in a procession from their centre to the town.

Stage on a hill slope at Almora, setup for open-air Ramlila shadow-play in October 1941. Culture centre student Guru Dutt played the role of Ram.

Another memorable function she remembers was the diksha ceremony, when Ravi Shankar officially became a disciple of Alauddin Khan Saheb. He learnt to play the sitar from his guru. A ganda (a red sacred thread) was tied to his wrist, Ravi Shankar touched the guru’s feet and an elaborate pooja was performed. After that everyone got a rasogulla as prasad. All the children remembered this. Rasogullas were a very special treat and perhaps not easily available then in Almora then.

After that the Centre hosted a series of weddings of their members. The first to get married was Ravi Shankar. He married to Alauddin Khan Sahib's daughter, Begum Roshanara, in 1941 who was given the name “Annapurna Devi“ after her marriage. Rajendra Shankar got married to Laxmi Sastri.

Everyone thought Uday Shankar would marry Simkie who was a gifted dancer, performed Bharatnatyam flawlessly, and was Uday Shankar’s partner in most dances. So it was a surprise to all when Uday Shankar got married to Amala Nandy.

Uday Shankar with his glowing bride, Amala, in a red Benarasi silk saree, shortly after their marriage in 1942 in Almora.

Simkie got married to a culture centre student, Prabhat Ganguli, who was a gymnast and a dancer.

My mother recalled, “While the pandit conducted these wedding ceremonies we were too young to differentiate between a real event or theatre. We thought it was just another performance. All we remember is that after each wedding we were given a rasogulla. That was the highlight of the event for us!”

Zohra Begum with culture centre student Kameshwar Sehgal as Shiv-Parvati. They got married in 1942 in a civil ceremony at Allahabad.

The first All India Music Conference took place in the Centre in Almora where maestros like V. G. Jog, Patvardhan, Bal Gandharva, Master Madan, Narayan Rao Shankar Pandit, Onkar Nath Thakur and Prem Ballabh Joshi were present. They all came to participate in this conference. Prem Ballabh Joshi inaugurated this historical music conference with his sitar recital. Apart from musicologists and artistes, very few people know that Prem Ballabh Joshi was a renowned musicologist of his time and a sitar player of a very high order, because he died fairly young. Soon after this conference, Master Madan also died at a very young age.

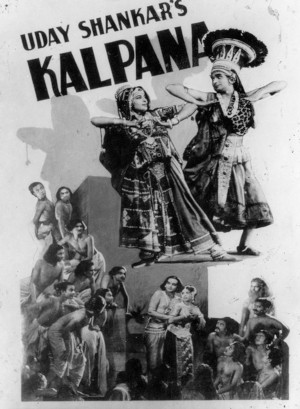

In 1942, Uday Shankar decided to make an ambitious film “Kalpana”. Sumitra Nandan Pant was asked to write the lyrics of the songs. However the film did not run and huge losses were incurred. Around the same time, a few conservative residents of Almora who were critical of the Centre’s activities from the beginning, grew increasingly vocal in their protest. “We don’t want our daughters to dance in public“, etc. It so happened that the local tension that was brewing in Almora coincided with invitations for Uday Shankar’s dance troupe to perform abroad. It also seemed the only way to compensate for their recent financial losses. Whatever the reason, once Uday Shankar left with his troupe for shows abroad, he never returned to Almora, and the Centre closed down in February 1944.

A great loss for posterity.

The poster for Uday Shankar's 1948 movie Kalpana. The film was digitally restored by Martin Scorcese's World Cinema Foundation and re-released in Cannes in 2012 with 93 year-old Amala Shankar in the audience.

Yashoda Maa and Sri Krishna Prem at Mirtola Ashram

Babban was also a serious spiritual seeker and very close to Sri Krishna Prem, Yashoda Maa and Dr. Alexander from Mirtola Ashram. Sri Krishna Prem was Babban’s friend and would often meet Babban in his pharmacy, “Medical Hall”. Sri Krishna Prem was the head of Yashoda Maa’s Ashram. Originally an Englishman, he became a Hindu and could recite the Geeta beautifully. His pronunciation was perfect. He was a sadhu and would walk barefoot from Mirtola to Almora. He often invited Babban to join in the annual Janmasthami celebrations at Mirtola and Babban would ride on horseback to the Ashram.

Yashoda Maa (1882-1944) was the guru of Sri Krishna Prem (1898–1965). She was inspired to start Mirtola Ashram near Almora. She was a Bengali, married to Gyanendranath Chakraborty who was the Vice Chancellor of Lucknow University where Sri Krishna Prem taught English. All three of them met often at Yashoda Maa’s house and were good friends.

Yashoda Maa began to have a recurring dream where she was explicitly guided to go to the foothills of the Himalaya and open an Ashram exclusively dedicated to Lord Krishna. The three of them left Lucknow to go on this journey but mid-way Mr. Chakraborty had a heart attack and passed away. Sri Krishna Prem and Yashoda Maa continued on the journey towards their destination. That is how Mirtola Ashram was established in 1930.

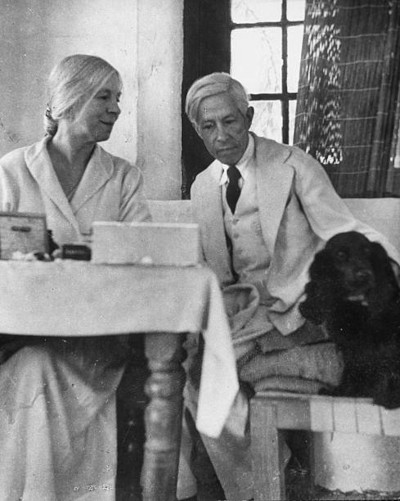

Yashoda Maa with Sri Krishna Prem at Mirtola Ashram.

The Radha-Krishna temple at Mirtola Ashram that Yashoda Maa built in 1931.

Whenever she came to Almora, Yashoda Maa used to stay at the artist Brewster’s house, and my mother along with her sister would often go to meet her there. My mother thought Yashoda Maa had the most beautiful face, a face that epitomized divine love and motherly care. She loved to hold my mother in her lap. No wonder my mother said she always remembered Yashoda Maa, not as a great spiritual mentor but as a warm, motherly, person full of affection. It was only much later when my mother grew older, that she realised how fortunate she had been, to have known someone so evolved like Yashoda Maa, at such close quarters.

Once my mother went to meet Yashoda Maa with her sister, and both girls sang a Krishna bhajan in front of her, “Dheerdharaiya/ peer haraiyya/ Krishna Kanhaiyya/ Tumhi to hoho“. Yashoda Maa was so pleased with this bhajan that she gave each of them a small brass figure of Krishna. Both my mother and her sister did not realise the value of their gift, and put the brass figures along with their other toys. Eventually they got lost. Many years later when my mother was reading Dilip Kumar Roy’s memoirs, she came across an interesting part in his book. Dilip Kumar Roy had written about his visit to Mirtola Ashram to meet Yashoda Maa, who had also gifted him a small brass figure of Sri Krishna. Dilip Kumar Roy placed it next to his bed, near a window. One night, he saw the brass figure, illuminated with a divine light. After reading this my mother regretted how she had carelessly lost Yashoda Maa’s precious gift.

Moti Didi was Yashoda Maa’s daughter. She taught my mother popular Bengali ditties like “Dhondhondhon/ Baditephooler bon/ “and so on. She also taught her the Bengali alphabets and got several books to help continue her learning the Bengali language. Babban taught my mother how to read those books. Moti Didi sang beautifully and taught my mother a powerful song:

Proloy nachun nachle jokhon, apon bhule

He Notoraj Notoraj!

Jotaye bandhon podlo khule

Roloy nachun.... He Notoraj, Notoraj!

Janvhi toye muktadhara

Unmadini shaye hara

Proloye nachun.... He Notoraj, Notoraj!

It’s quite amazing how my mother remembers these details of their meeting. It must have certainly left a strong imprint upon her young mind.

Dr. Alexander was another friend from Mirtola. He was also a sadhu and very strict about his diet. He used to have only 5 food items which included salt and water. He cooked his own food. My mother remembers that when he came to Almora from Mirtola to meet Babban, he would cook in their home outside the main kitchen; where an angithi (coal stove), cooking pots, and food stuff would be kept separately for him, so he could make his own food.

He would often say, “If you are a spiritual seeker, your goal is not accomplished in one birth. In your next birth, you will certainly go one step higher from wherever you are in this one. So make good use of this time on earth. What you have learned in this life will not be wasted. You are destined to take your learning forward into the next birth.“

Samadhi at Mirtola Ashram for Yashoda Maa after her death. Seated in front on the left is Major Alexander (Hari Das). Seated behind him (from L to R): Moti Didi, Frank Baines, Madhava Ashish and Keshab Priya. This photo taken in in 1946.

Babban and Chachi: The Homemakers

I enjoyed being with Babban. He created a warm loving atmosphere around him which meant home. Just like the tortoise who carries its home on its back, Babban too carried his home around him, wherever he went- with Chachi. So it was Babban-Chachi together which made the magic of the place called home. I am sure, just like me, all their grandchildren have also been sustained by their childhood memories- of the time they spent with Babban and Chachi.

Being the eldest grandchild, my memories go back a long way to the Almora home too, but they are a little blurred. Babban lived in his joint family, till family discord created painful situations and he was compelled to leave his home.

Babban as a teacher at Mussoorie

Babban had four daughters but only the eldest, my mother, had got married by then. So he left Almora and came to Mussoorie and began teaching Sanskrit and Hindi in the senior classes of a well-known school.

My grandparents' house at Mussoorie.

He got his job when he was almost near retirement age, and had never done a job before, but he had the moral support of Chachi’s father (Bappi - my great grandfather.) Even so, it must have certainly been a very challenging time for him.

Although basically Babban was a very positive person, his relationship with money was not good. Perhaps certain circumstances made him suspicious about the power of money. He had earned a lot of money when he took care of the pharmacy in Almora. But, by the time he came to Mussoorie, he felt money was the sole reason for the break up of his joint family, and the sole reason for having to leave his beloved Almora.

This must have got so deeply embedded in his consciousness that he literally became allergic to money. When he took up the job in Mussoorie after leaving Almora he was stricken down by severe eczema in his hands. The doctors could not help him. It was much later that he diagnosed the root cause of his skin disease; that his eczema occurred and got aggravated only after he touched money in the form of cash. This was true.

He was unable to continue with his job because of the raging eczema in his hands. When he left his job and my eldest aunt started earning, his eczema subsided and soon disappeared.

That is one reason why, after all his daughters were married, he began to stay turn by turn in his married daughters’ homes. Both Babban and Chachi were great assets to the homes they visited. He would teach the children Sanskrit shlokas, tell stories, teach songs, and of course have daily musical baithaks in the evenings.

The atmosphere of the house he chose to visit, would be completely transformed. Chachi would take charge of the kitchen and general supervision; so all his daughters looked forward to their arrival.

Once, I overheard Chachi telling Babban that it was wrong on his part to give up all his family inheritance. She said that if she had some personal money she would like to give something to her grandchildren if not her daughters. I overheard Babban comfort her by saying, “Our presence in their homes is invaluable compared to any amount of money we could have given our daughters. I have realised that money makes a person arrogant, and it always takes away happiness. As a matter of fact, it brings more unhappiness than the happiness it gives. Life is short and changes constantly. Everything is temporary. This is a good way to live, moving from one daughter’s home to another. Change is the one permanent truth of life.“ Chachi had no answer to this.

Fortunately by then his daughters took over the responsibility of running the house. It was almost as if by some divine intervention, someone had designed their lives to perfection. Turn by turn each daughter got a teaching job in a college or school; and just when she got married, by a stroke of providence the next daughter got a job and so on till all the daughters were married. At this point time I was enrolled into a school in Mussoorie and spent some really happy years staying with Babban-Chachi till I passed school.

Babban and Chachi visit Gwalior

I must share this story of how I changed my name. It is related to Babban. I was very young, maybe all of five and half years of age and had not started school. I was the eldest with no siblings then. Babban was staying with us for a month or so. We were in Gwalior. It was summer and we all slept outside together in separate cots under mosquito nets- on the rooftop or chhut. During summer days it was customary to pour a lot of water with a hose onto the stone floor to cool the air. Early in the morning, I would get into Babban’s bed and he would regale me with stories. Everyday he told me a story about a different girl. This girl would be my age but each day she had a different name. One day it was a story about a girl called Sunita or Meera or Shanti, etc. This girl was an ideal girl who did all the right things.

So if he started with a story about Shanti, he would begin with “When Shanti gets up in the morning, the first thing she does is brush her teeth“He would give a meaningful pause at this point. I would promptly get out of bed and quickly brush my teeth and get back to him. Shanti’s story continued the whole day. I would do whatever Shanti did, bathe, have green vegetables, and whatever else good girls did. But I had one condition. I was Shanti for that particular day and Babban and my mother had to call me Shanti. If they did not, I would pretend not to hear. They indulged me and we continued this game. Each day I was a new girl with a new name: Meera, Sunita, Nidhi. I enjoyed it and all the attention.

Within a fortnight of his stay there, I was taken by my mother to get admitted into school nearby. That day Babban had told me a story about Anuradha so I was Anuradha. Simple. While filling the form, the Principal casually asked me my name. I replied “Anuradha“ but my mother said “No, No her name is Meenakshi. We call her Meenu at home. Please write Meenakshi.” I do not remember this clearly, but it seems that I started crying and kept saying, ”Today I’m Anuradha! Today I’m Anuradha!“The Principal said “Oh well. Anuradha is also a nice name. “And she wrote ‘Anuradha’ in the admission form. My mother agreed because she felt it would seem distinctly odd to narrate the long story about my name to the Principal.

The next day I was back to playing the same game with Babban, with a different name. But as I had joined school, Babban and I had less time together. Soon after, Babban left Gwalior after a few days. Although I never played this game again, I was stuck with the name “Anuradha“ for life.

Talking of name games, Babban had this habit of giving different names to commonplace things at homes, of course with our consent. So we all had a personal connection to those things and definitely added to our family bonding and amusement. There were several such names and some incidents were quite hilarious. I can give one example. Babban, Chachi and my aunts were strict vegetarians. Eggs were forbidden in the house. But as I ate eggs, a concession was made on my account. Eggs were allowed into the house, if everyone agreed to Babban’s small but weird request: that we do not not say the word “anda“ while referring to eggs. He disliked the sound of the word ‘anda’. He thought it sounded crude. There was no reason really. Instead he asked us to call an egg “afsaana!“ We indulged him but amidst a lot of giggling and of course we happily had many “afsaanas”.

Babban and Chachi visit Rishikesh

Once we had gone to Rishikesh and we were walking across the Laxman jhoola amidst a huge crowd of people.

Lakshman Jhoola at Rishikesh in the 1950s.

We couldn’t see Chachi but thought she may have lagged behind us. Suddenly I spotted Chachi in a boat crossing the Ganga river below the jhoola. I waved out to her, and she waved back happily. Babban said “Look at her. She didn’t tell anyone. She is such a tomboy. She could get lost. She doesn’t think of anyone “He was upset and scolded Chachi for being irresponsible. Chachi said nothing. She wanted the boat ride but knew Babban would never agree to it. She went right ahead and did it.

Babban and Chachi at Haridwar

There is another hilarious incident I remember vividly. We were visiting Babban- Chachi. They were staying in Haridwar, as my aunt was teaching Sanskrit in a college there.

The houses were built very close to each other and the roofs of all the houses touched the roof of their neighbouring house. The monkeys had a field day jumping from one roof to another in the daytime.

The house we stayed in was built in a haphazard manner. There were three large bedrooms - one room on each floor- so we had to climb a lot of steps to go to the rooftop. Chachi would leave a lot of foodstuff there on small charpais to be sun dried, like jars of pickles, mangoes and badis, etc.

All of us slept in one bedroom. It was a good arrangement because after an early dinner, we would all lie on our beds, in the dimly lit room, and narrate what happened during the day, and have conversations about future concerns like my aunt’s marriage.

One evening there was a loud sound from the room above our bedroom. Then the sound got louder. Babban sat up and began shouting “Kaun Hai ? Kaun Hai?” He did not get out of bed.

Meanwhile, Chachi slipped out of bed, opened the door and went up the stairs. Babban kept saying “Chachi! Stop! Don’t go up! Stop Chachi from going up!“

Nobody did or said anything. Then there was a loud clattering sound. And after that, complete silence.

Babban kept calling out to Chachi, but neither my mother or Babban got out of bed.

Then I saw my aunt quietly getting out of bed, out of the door and up the stairs. I followed her. I thought that Chachi may have met with an accident. But when I went halfway up one flight of stairs, I saw a strange scene. Chachi was sitting on the topmost stair laughing helplessly, with her pallu around her mouth to stifle the noise of laughter. She signalled me and my aunt to be quiet, and we sat down next to her.

We learnt- in whispers of course- that a group of monkeys had descended onto the rooftop and toppled the charpais so the contents fell down. That was all. Chachi went with a stout stick and shooed the monkeys away. The mystery was solved.

But I wanted to know why she had remained silent when Babban called out to her. She didn't answer but continued laughing quietly.

Meanwhile we could hear Babban still calling out to Chachi, from his bed. Neither Babban nor my mother made any attempt to get out of bedand come upstairs. When we finally contained our laughter, we decided to go down.

“What happened? What happened?“ Babban asked in an agitated manner.

“Nothing,“ said Chachi.

Babban got more agitated. “What do you mean nothing?“

“Monkeys,” Chachi answered in one word.

“Monkeys?” Babban nearly jumped at this answer. “Only monkeys! Then why did it take you so long to come down?”

Chachi did not answer.

“And why were all of you so quiet?“ he asked.

Chachi replied “We just sat on the stairs”. With that she turned off the light. My aunt and I continued to stifle our giggles.

Babban kept mumbling how Chachi was not concerned about him and how anxious she made everyone, and how Chachi just wanted to have some fun at Babban’s expense. Chachi did not answer. That was Chachi.

Anuradha Joshi's maternal grand parents: Shri Kanti Ballabh Pant ("Babban") and Smt. Ganga Devi ("Chachi").

Babban and Chachi at Mussoorie again

I was a lot older, when I went to stay with Babban, Chachi and my aunt, in their home in Mussoorie. I had to complete the last two years of school. It was undoubtedly the most wonderful time of my life.

There was always a lot of music around the house. Starting from Babban’s Vedic chants in the mornings while he was still in bed. As the weather was always a little chilly in Mussoorie, even in summers, the bed was the warmest and most comfortable place. He always said that if someone was genuinely curious, the Rig Veda contained all the answers. Sitting upright was essential, when he chanted the Sanskrit shlokas. He would also deflect his hand forward, back and other directions. I forget the exact way. The rhythmic chant had to be pronounced accurately with certain syllables stressed more than others. He regretted that a lot of this knowledge was getting forgotten. Sound was all powerful. So the correct sound of voice, pronunciation of words, pauses, intonation, stress on syllables, and movement of hands created a combination that unlocked one’s potential and could make miracles happen.

During those days we were staying in an old cottage made of a crude mixture of mud, wood and scraps that were held together. This was how walls of old houses in the hills were traditionally made. However there had been no maintenance and it was in a pretty run down state. The floor had little holes in places, but it was not dangerous as it was built on stilts. It was merely a social embarrassment to me if my friends came, which was rare anyway. Otherwise we were comfortable with it. Babban had named these little holes “pol“ and very often Babban- Chachi and my aunt- and I would laugh when we discovered a new pol on the floor and say “pol khul gayi“. (it also meant that our ‘secret is out now’). In retrospect I wonder how we could laugh at these incidents in such a carefree manner. But living with Babban was like that.

I was 15 years old, and was at the foolish stage of life, when I tried my best to conceal my ignorance with cynicism. I would bluster and say I do not believe in magic. But Babban believed that the power of his chanting could transform anything into reality. It could seem like magic but it was deep faith and the power of sound that worked like magic. I immediately told him that I would believe him only if he could transform our old cottage into a nice house. He agreed, and said he would try but he would have to chant for several hours. True enough he began his chants after dinner, till early morning.

That night we experienced a terrible storm, like one I had never experienced before. There was thunder, lightning, fierce rain which got worse as the hours went by. One could hear noises like trees toppling and a tin roof crashing and so on. Babban continued his chanting through all the noise. When the storm began, my aunt and I were at first, quite amused and giggled helplessly as it became worse. We were anticipating how we would tease Babban in the morning. Later both of us grew anxious when the raging storm showed no signs of abating. We wanted to ask Babban to stop. But he was in a strange trance-like state. At some point during the storm, we must have drifted off to sleep, to wake up the next morning to a clear and calm sky.

When we stepped out of our cottage we saw that trees had been uprooted and the tin roof of our cottage had blown away. It was sad to see it lying a little distance away, completely damaged. The cottage which was always in need of repair was now in very bad shape. The storm had ravaged several smaller buildings around us. Our cottage was part of a larger estate. As It was impossible to stay in that cottage, even for a day, we were temporarily shifted to a larger house on the estate, for a very nominal sum of money.

Mussoorie during the mid sixties, had several large estates with empty houses. If the owners knew the person concerned, they would take an absurdly small amount of money as a token amount as annual rent from their tenants. The annual rent for the earlier cottage was only Rs. 150/- a year. After the storm, we spoke to the owner who was staying in Dehradun who agreed to let us stay in the larger house in the same estate, for Rs 200/- a year! We agreed. It seems quite unbelievable today.

We were all busy, that day shifting our belongings and the odd pieces of furniture, into the new house which was right next door. We were very happy to have such a smooth transfer, all within one day. After all the excitement was over, my aunt and I began teasing Babban and asked him “What happened Babban? Your chants produced a raging storm instead of producing our house?“

Babban sheepishly answered that this was ‘kalyuga“ and hadn’t he always told us that we had forgotten the right inflection and the correct movement of hands. Perhaps he too had lost all that knowledge. He sounded so disappointed that we did not have the heart to tease him any further.

Both my aunt and I would remember this incident and have a good laugh with Babban and he would also join in saying “Oh! I do this only to entertain all of you. Just to make you laugh.”

Many years later I was narrating the same incident to a friend. I expected him to laugh at the end of the story. Instead he said, “What a wonderful story! It shows clearly your grandfather proved the power of his chants, didn’t he? You shifted into a better house the very next day. What better proof could he give you?“

I was dumbstruck and wondered why had it not occurred to me. Of course, it made perfect sense when he said it. Strangely, this incident had never struck me in such a way before. After so many years, Babban’s belief in Vedic chants had finally been validated. Babban had been right. I only regret that I realised it so late. Sorry, Babban.

As I said earlier, Babban started his day with reciting the Vedic shlokas. Then he would hum some raga to himself. He used to write bhajans, horis, and folk songs and set them to music. In fact when they were in Almora, my mother remembers even simple conversations between Babban and his four little daughters would always be a musical exchange. Words would automatically fall into rhyme and rhythm. It must have been fun to converse like that. In the evening the whole family would sit down together and perform a symphony created and directed by Babban. I still have vivid memories of it. Each person would participate. Babban would play the harmonium, my mother the flute, one aunt the sitar, another aunt the violin and Chachi would play the tabla. This symphony was sweet and simple but the vivid memory of the whole family making harmony together is something I can never forget.

My mother says that in Almora, Babban also helped the children produce a home magazine called “Nakshatra“ in which all the children: my mother, her sisters and all the cousins would contribute and Babban would help them in putting them together. He was also a good artist. When he was ill and there was little money to spare, just before he finally left Almora, he would ask Chachi to save up all the burnt matchsticks in several match boxes and use the matches to make tiny sketches with them. One of my aunts also inherited his talent and she too had a small pad where she made beautiful sketches in black ink.

When I was staying with Babban-Chachi in Mussoorie every evening without fail, Babban would ensure that we continued with our evening family get-together. We would start with a 5 minute prayer, which was a collection of Sanskrit shlokas from the Geeta, specially chosen by Babban. This was followed by a 5 minute meditation session. Each of us was asked by Babban to think of something that had totally preoccupied our time, the entire day. It could be anything: our favourite book/ food/ vegetable/ friend or even an incident. We could choose anything but we would have to pay exclusive attention to that particular thing for 5 minutes. That was ‘dhyaan’. When it was over he would ask us if we had succeeded in paying attention without distractions. If we were distracted by something the next evening we would be asked to focus on whatever had distracted us the previous day.

After that we always had a family song. Each week one person was given a chance to choose their favorite song which we would sing together, for a week. The next week was another person’s turn. Usually bhajans were chosen by Babban, Chachi and my aunt. But, when it was my turn I always chose a popular film song; usually a love song. I wanted him to feel a little uncomfortable about my choice. But on the contrary he felt happy, and would break the song into small parts and tell me how that particular part was based on a particular raga. Even today, many times I remember the raga I had learnt while singing our ‘family’ song.

After the family song we would spend time talking about our dreams the night before. Babban took dreams very seriously. Each morning he would spend at least half an hour with Chachi after breakfast to discuss his dream. He usually had dreams. Chachi said she never did. But she listened patiently. He would analyse and make sense of disconnected events in his dream by thinking aloud- with Chachi as his audience. Babban said his dreams had often guided him to resolve a problem or choose the right course of action. In the evening my aunt and I could discuss some compelling dream if we still remembered it. (It was only on Sunday mornings we had the time to have a detailed discussion about our dreams). Every evening, we would also talk about the events of the day. My aunt and I narrated some incident from school and Chachi would ask us what we would like to eat the next day. If Babban had written a fresh piece of writing he would read it out to us. Or sing his new composition and tell us that he would teach us the next day if we wanted to learn it. He was fairly easy going about most things.

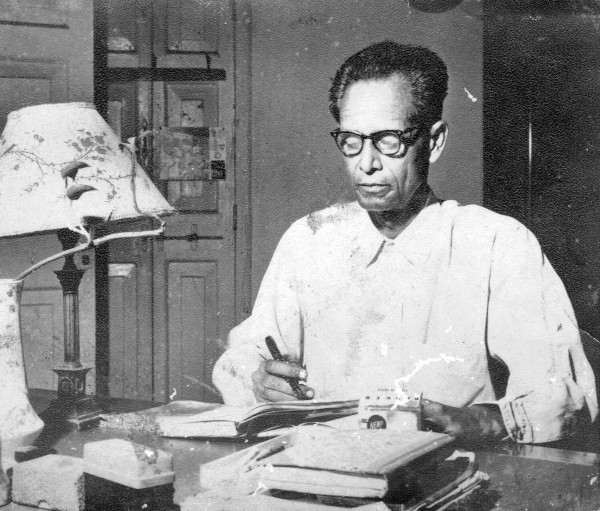

Anuradha Joshi's grandfather, Babban, at his writing desk.

Except for one complaint. He was very keen to teach the Patanjali Sutra to his wife, his children and grandchildren and none of us were willing to learn. He had given up on Chachi long back. Chachi was busy doing all the cooking and housework where we all pitched in to help, but after it was all done she did not want to hear a lecture on the essence of Patanjalisutra. Instead she preferred to sit down with a pack of cards and play a game of patience. Babban could not see very well and so it was a simple arrangement. While Babban gave his long lecture on the sutra, Chachi would actually be engaged in doing something else and yet dutifully make the right noises to show that she was listening. Sometimes she would get caught and Babban would throw up his hands in disgust and repeat his favourite phrase in Kumaoni “Kathekuncha, kekuncha“(To whom can I speak? What can I say?) This was his constant refrain. Even with me. He thought my young fertile mind was the right soil to sow the seeds of Patanjali Sutra. Unfortunately I was at that stage when I resisted any efforts on his part to enforce any learning he felt was good for me.

I was a rebel without a cause, because he was not at all the kind of person, who ‘enforced’ anything.

I regret that phase of my life because the loss was entirely mine, proving the truth of another of his pet pet phrases: “Akkal aur umr ki bhent nahin hoti.“ (Wisdom and age never meet.)

When I was in Mussoorie, we played a familiar game with one another. Babban would be lying in wait for me - to return from school - to become his audience. Just like Chachi, I too was reluctant to hear his lecture on Patanjali sutra, immediately after school, so I always sneaked into the house from the back door. I knew he was waiting for me behind the main door ready to pounce on me with his shlokas. I also knew it was a mean trick to play and that he would be disappointed. I would hear him saying “kathekuncha, kekuncha“ in a loud voice, so I could hear.

The collection of shlokas that Babban taught us to recite, meant a lot to him. He often said, “I have no money or property to leave behind. Money and property bring discord in families. These shlokas that I have taught you to recite, is what I’m leaving behind. This will protect you. There is power in sound and they will create bands of iron around you and keep you safe. Have faith in them. They are my legacy. Ask your children to learn it and take them forward.

That is how I want to be remembered.”

That was Babban.

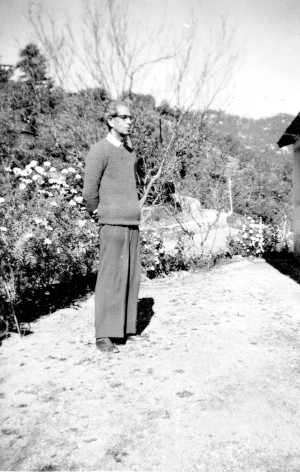

Anuradha Joshi's grandfather, Babban, in the garden of his house in Mussoorie.

Comments

Beautiful narration

Dear Anuradha Didi,

I came across this page because of Mitu's FaceBook post and I really enjoyed reading it. Once I started I read it fully. Your style of narration is so nice and endearing. Please do share more such articles, I am forwarding the same to Sheila to consider these as reading material for students at Abhibhavak Vidyalaya.

Ashok

My memories of Mussoorie

Thanks Ashokji.. Glad you you liked it

It's a good idea to use it for school

Anuradha ji's writings

Anu ji's writings come straight from the heart and raw experience. How wonderfully and endearingly narrated. Of exceptional simplicity and aesthetics. Please write more.

MY MEMORIES OF MUSSOORE

Exploring Mussoorie Inside out

By Jatinder Sethi

Anuradha it was just by chance that I came across you through your blog while googling myself hor a piece I am trying to write about my own life after my head operation. And I am asmed to tell you that I have a small piece on my visit to Mussoorie long time back,posted on web of www.ghumakkar.com. Your piece has brought my old forgotten memories of Udasy Shanker ,Sumitranandan Pant and Dinkar of my college days. I read your piece twice and forwarded t to some others. You have gem of old photos ,at least for us older people who have listeneto all the great people in your blog.I visited Almora twice with my famil while on annual holidays from my work in Bombay.Tday at 90 I am in piece. Gurgaon and I was trying to write my life after my head operation in Medanta that I came across your piece. Who should I thank..Google or Subhash. Greatto knw you

Mirtola ashramites

Dear Anuradhaji,

Thank you for sharing this wonderfully written reminiscence. I really enjoyed reading about Bappi, Babban and your entire family.

I am particularly interested in the section about the ashram at Mirtola, as I am currently researching the life of Sri Krishnaprem.

Do you have any more information about Frank Baines and Keshab Priya? I am familiar with Moti Rani, Haridas and Madhava Ashish, of course, but this is the first time I have come across mention of either Baines or Keshab Priya.

I would love to know more about them, and the photo above, if you can help me. If you would rather email me I am available at jonchapple@gmail.com.

Thank you in advance for your help!

Jon

Very well written. Gives a

Very well written. Gives a graphic account of the life in the hills and a glimpse of the great persons who lived and enjoyed the salubrious climate of the hills. Having lived in Missouri for five months as a trainee, I felt nostalgic. Thank you for the article.

Mussoorie

I came across your memories of Mussoorie. I spent 16 years teaching in an International school there and have written many poems about the flora and fauna of the mountains. I hope we can connect and share experiences. It was my home and where my daughter was born at the Landour Community Hospital. So she calls herself the Mussoorie baby!

My memories of Mussoorie

We should certainly share memories with one another.lets keep in touch.

How many years ago were you teaching

Hello,

Hello,

I thoroughly enjoyed your old photos. I have collected many old photos from Landour and Mussoorie and put together a book called "Then and Now", matching them with current day shots.

I love the place and history, having lived there for many years myself.

I was wondering if you'd like an electronic copy of an old Survey of India map of Mussoorie rom 1947, which features your grandparents old place in Barlowganj.

If so, please email me. Of course, you may already have it?

Best regards,

Mark

Add new comment